There is no longer any doubt about it. We are at a decision point in history. We are nearing the point at which we have the opportunity to throw the switch on the tracks of history to go down a new path. However, I fear we as a people are too busy with our necks craned down to look at our screens while the switch passes by us and we head down the tracks to major war abroad and on our own shores, upheaval we have not known since before World War II, and a major collapse of the social order which has been slowly eroding for three decades.

Ok, ok. I know some of you are thinking that this is some post-election emotional diatribe. Nope. Nothing of the sort. Please read on.

Matt Cavanaugh provides an excellent analysis of William Strauss and Neil Howe’s, The Fourth Turning, which predicts generational cycles based on sociological changes in how people feel about themselves, authority, and structure. The authors predict we are at a point in our history – a turning – where we will see a “decisive era of secular upheaval, when the values regime propels the replacement of the old civic order with a new one”.

This is a very interesting analysis of a theory of sociological cycles in history. It is difficult to argue against the methodology and description of where we are. What I’d liked to have seen is a discussion of how information, networking and technology fit with this prediction. I can probably make a case that it could exacerbate the decline into the “winter” the authors predict. Maybe could make a case the other way. It’d be a great discussion.

But I think that Strauss and Howe are probably right in this case. It is certainly beyond argument that we are seeing what Strauss and Howe predicted in 1997. They said we would see a breakdown in trust, which is exactly what we see from one poll to another. Robert Putnam shows that the values regime of diversity and multiculturalism actually reduce trust in the United States. This is a stunning claim that many would find difficult to accept (look at some of Putnam’s evidence here, here, and here). But when we look around, and when we are honest with what we see, as opposed to what we say should be, we see societies separating into those who look or think alike.

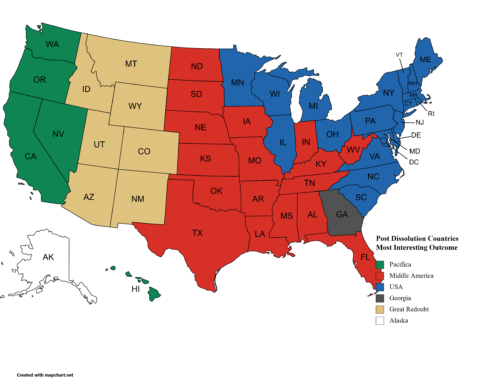

America is now deeply divided. There was a time when immigrants lived in an immigrant quarter because that is where they could find affordable housing near jobs in cities. Today, once again immigrants live where they can, but that is often far from jobs. And those that can, segregate themselves in neighborhoods more and more homogeneous than ever. Homogeneous by race, by class, and by political affiliation.

This self-segregation is powered by the information revolution, which affords people data they never had in the past, and which they use in ways they may not even realize. But the reality is that people use this access to information to be near those like them because, as Putnam shows, whether there is cause or not, people don’t trust others as much as we think they should.

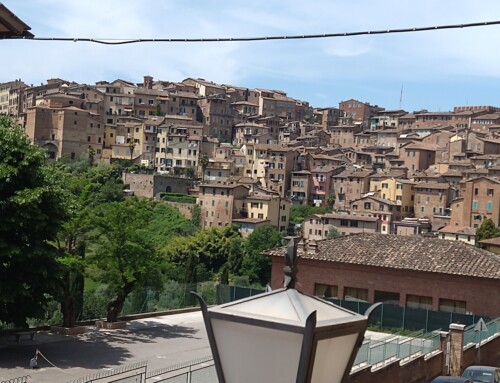

And it isn’t just here in the United States. All over Europe, countries are seeing a rise in nationalistic sentiments stronger than any time since the post-Napoleonic nationalistic rise across the continent. Europeans were fine with the concept of integration when it meant buying affordable goods they couldn’t prior to open borders. They were fine with diversity when that meant English vacationing in Spain and France, or Germans vacationing in Greece.

But when Turkey sought admission to the EU, integration wasn’t so great. When Bosnia’s Muslims emigrated to Sweden and Germany during the Balkan wars of the 1990s, that was fine because they were secular Europeans. When Chancellor Merkel pushed her fellow European leaders to accept hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees, they balked, arguing that Middle Eastern Muslims wouldn’t integrate. And when untold numbers of non-Syrians flooded into Europe and crime rates went up, nationalist leaders gained in polls across Europe.

Strauss and Howe predict much more than the decline in public trust. They predicted war. They predicted very destructive war. And while people disengage from each other and the world around them as Putnam described due to the personalization of entertainment, the world becomes more dangerous. Paul Miller, writing in Foreign Policy, makes a case for how Russia could push the US and NATO into World War III in Latvia. At the same time, North Korea races to develop an ICBM capable of carrying its nuclear weapons, Iran threatens to use the very weapons they continue to develop against Israel or Saudi Arabia, and the US challenges China’s claims to the South China Sea under the notion that any conflict with China would stay local and not come to our shores. Most Americans would be stunned in disbelief if a country we routinely bomb has the audacity to bomb our homeland in response.

In his outstanding, 1913, Charles Emmerson provides a sweeping survey of Europe in the year before the Great War (World War 1). The most important take-away from Emmerson is that war was really unthinkable to the people of Europe, despite their making it all but inevitable.

Likewise, if we find ourselves in a huge mess of war or civil strife, there will be countless people asking how it came to pass and countless articles feeding their misery. And when the next generation recovers from our weapons and destruction, there will come another Turning and the cycle will start again. They will strengthen institutions and accept weakend individualism just like our forebears did after the Revolutionary War, the Civil War and World War II.

Despite the fictional narrative of American “rugged individualism” people recovering from devastating war and civil strife rebuild through community. Perhaps it isn’t too late to build a genuine community as so many idealists (I’m one) hope for. But the realists (I’m one) may be putting the country and world back together in the next couple of decades.

Either way, God help our kids.

[…] real news and disinformation, especially deep-fake videos. We finished November 2019 with a call to take action now to stop the slide towards the unrest that was so evident then and has begun to manifest since […]