At a recent Sunday family gathering, a young extended family member was telling of his apprenticeship as an electrician. Six months out of high school, being paid to work and learn the trade, he will test out of his second year of apprenticeship in another 6 months and be a certified journeyman. His firm wants very much to keep him. Another firm started by his first mentor wants to hire him away. The general contractor on the major project he’s working on already comes to him for questions instead of his nominal supervisor.

This young man is learning skills that will keep him gainfully employed throughout his life with zero college debt. He will earn above the median income and will be his own boss. This is what every young person today says they want. He is making it happen.

At the same time, my new neighbor, recently moved from California, cannot find a contractor to come build the addition to their home he so desperately wants. He cannot find a concrete guy to even come give him an estimate. My own concrete guy who I recommended can’t get away from his jobs to come give an estimate for what will be a very small pour for him. My neighbor is not alone in his inability to find contractors.

The issue isn’t information systems for job needs. Word spreads through communities when people need work and when people have work that needs to be done. The problem today is that few remain who are willing like our young family member to take on a trade. The culture tells them to learn Python and make a living coding. The culture tells them to go to college and grad school to get a high-paying job in the intellectual economy. But the culture also wants and needs work to be done around their homes and offices.

That delta between what the culture says people should do and what people need is now great. Hence we have contractors that are so busy they can work all day every day if they desire to do so, and those with need have difficulty finding someone to do the work. And as the previous generation of builders, contractors, electricians, plumbers, welders, mechanics, and all other tradesmen age out and retire, there are vastly fewer people to replace them.

The issue of the population fighting for a limited number of jobs in white collar fields leading to a superabundance of baristas with fine arts degrees and huge debt loads while engineering and construction firms desperately needing workers is real. Technical colleges are growing at great speed and with help from local manufacturers. Our local technical college recently expanded and built an advanced manufacturing center. The jobs climate is such that whoever enters the program is guaranteed to be hired upon graduating by local industry.

Of course it is possible that this sudden need will turn some people’s preferences from white collar to blue collar work. When miserable office workers or call center workers hear about contractors making multiple times their wage, it is entirely possible some number of them will move to trades. “It is considered a second choice, second-class. We really need to change how people see vocational and technical education,” Patricia Hsieh, the president of a community college in the San Diego area, said in a speech at the 2017 conference for the American Association of Community Colleges.

But it isn’t just the trades workers that are needed. There is an ongoing recognition that truck drivers are a key to America’s present supply chain crisis. While the New York Times says there is a shortage of drivers that is affecting all facets of logistics and delivery, Time says there are far more qualified truckers than there are positions in the country. Smart Trucking says the issue is that truckers quit because they are so poorly treated and compensated. So nit picking aside, despite the many people people in the country with a CDL, there is a great need for more people to transport our goods the first mile out of the ports and the last mile to our homes. So when logistics managers figure out that they can retain good people with a bit more care and pay, perhaps the equilibrium will reset.

So what happens moving forward? How will the homes and towns that were destroyed in December’s tornadoes in Kentucky be rebuilt when the there were already few builders and contractors. It is entirely conceivable that some of these towns will simply not rebuild and that people will move to other locations if contractors don’t exist to rebuild them.

And yet the migration to small cities and towns continues at great pace. According to The Economist:

“from March 2020 to March 2021, around 600,000 people moved from large, high-cost metro areas to mid-sized cities (meaning those with between 500,000 and 2m people), and more than 740,000 moved to rural areas, small towns and cities with populations below 500,000—an increase in both instances of 13.5% from pre-pandemic levels.”

So what happens if or when we have this next great sort away from big cities to smaller cities and towns and there are few who know enough of traditional skills to pass them on to the next generations? What if that shortage of practical skills is exacerbated by some natural catastrophic phenomenon like the Carrington Event that takes down power in the entire hemisphere or a massive volcanic explosion that prevents crops from growing for two summers? Is it possible that we undergo some dystopian future as written about in Miller’s A Canticle for Liebowitz or Fforde’s Shades of Grey? I find both these novels fascinating because they reveal where we very possibly are headed without ever intending to.

Jasper Fforde imagines an alternative future in which everyone is aware of the “Something That Happened” in the “pre-Epiphanic World” but nobody asks questions. There are remnants left over like the Carravagio titled Frowny Girl Removing Beardy’s Head. There is perpetualite (asphalt roads from before Something That Happened) and reservoirs held back by dams that someone had obviously built.

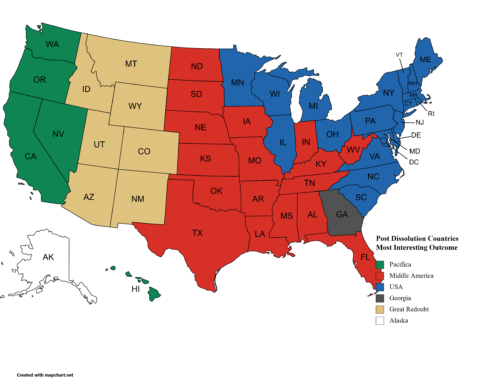

Two features of society mark Fforde’s dystopian future. One is that society is organized in a hierarchical caste based on the dominant color a person sees with reds at the top and greys at the bottom. While comical in trying to explain why whole countries in the past saw certain colors (as is evident from coloration on a surviving world atlas) and how that diffused out to individuals today, the reality of the caste system even in a liberal democracy is very real. The educated and wealthy know their place and the uneducated and poor know theirs as well. The wealthy live where they wish and do as they wish and the poor live and do what they must to survive. Only in novels can we say as much so openly.

The second defining feature of Fforde’s future is that any desire to know why is a threat to the established order and is suppressed. When the protaginist is shown The Fallen Man, obviously the disintegrated remains of a pilot in an ejection seat, he asks, “Where did he come from?” He is told, “With all the unanswered questions kicking around, the arrival of a strange man strapped to a metal chair is of little significance.” The protagonist responds, “Perhaps the bigger mystery is that no one seems eager to find out. What do you think?”

If Ross Douthat is correct in his cultural critique, Decadent Society, we are becoming that dystopian future now by absent-mindedly and unquestioningly consuming information and not creating new inventions any longer. That has dire implications for our future, perhaps one that resembles Fforde’s more than we would care for if presented with that as a possibility. Fforde describes a mural in a civic building depicting The Dispersal of the Treasures, The Expulsion of the Experts and The Closing of the Networks. While we aren’t at the third one yet, it is arguable that we’re well under way with the first two. And if you follow any social media, you’ll see advocates for the third on both political extremes.

Walter Miller, writing two generations before Fforde, also envisions a future in which our successors have to rebuild from scratch after suppressing or killing off scientist, academics and anyone remotely responsible for getting humanity to the point where it developed the means to nearly destroy itself. Humanity deliberately and quickly reverts to an earlier state bereft of technology. Some scraps of knowledge are preserved and studied by monks for future use while over centuries science is rediscovered. Mankind slowly rebuilds itself over two millennia to the same point as it was when the space race and nuclear missiles first threatened humanity. You can guess the results the next time around are different motions leading to the same end.

If we really are doomed to go through historical cycles, then maybe the best way to preserve knowledge is to federate it out in communities as broadly as possible. Whether we lose our collective knowledge as in the dark ages when libraries were burned by invaders or through through decadence and low birth rates and lack of study in trades, it seems that the many will be dependent on the very few to relearn and rebuild. To that end, those communities that build up some capacity for resilience set themselves up for weathering the broadest possible range of future scenarios.

That is because no matter how bad a situation is, apart from a mass extinction event like an asteroid collision, there will not be a total collapse of humanity. Some remnant of civilization will continue, with great difficulty. It won’t be from one place either. There will be numerous towns and cities that slowly rebuild with whatever means they have.

We’re not talking doomsday preppers here. Not storing two years worth of canned foods or building luxury hippie condo communes in underground nuclear missile silo complexes. But small towns with diverse skill sets and cultures of sharing and carrying the load. Neighbors helping neighbors put up a shed or a barn. Homesteaders helping new arrivals learn how to garden or plant an orchard. Someone in the village building up a library so that knowledge is preserved locally. Someone knowing wild plants and herbs while others know and teach meat preservation or laying hedges or wood joinery using manual tools. Animal husbandry will be a great and valued talent. Those few horse, donkey and mule owners will start breeding and selling their animals for work and transport. It may take two human generations but they will spread.

Our ancestors knew these skills and prepared the world for our success. It is entirely possible to do so again in the face of disasters. But it will be much harder if there are few people with skills. It is conceivable that some places where craftsmen still live and teach will rebuild much faster than other areas. It is also very likely that many other places such as big cities will see terrible out-migrations because so few people there know any skills that will be practical without computers or electricity. Furthermore, in any long-lasting major power outage or disaster, the very food that cities rely upon simply will not be transported, if it is even harvested or grown. Toilets will not flush absent water pressure. Lumber for repairs will not be milled and distributed. Police will not keep order.

It is in the towns and villages of North America and the world that we will need to look if we ever get to a point in the future when humanity needs to rebuild. The question of how it happened is only interesting to think of beforehand. The question of why we need to rebuild won’t be asked. The question of who will be around to teach and who will be willing to learn will be everything. When there is no YouTube to watch how-to videos and no electricity to power a lathe of a bandsaw, people will have to seek out those remaining older people with skills to teach them how to carry on. Perhaps a deliberate effort to seek out those people with practical knowledge and books for future library shelves is the first step to future human rebuilding.

Leave A Comment