I was listening to NPR this morning when a story came up about the new status symbol in the US these days: Busyness, or at least the appearance of being too busy for leisure and other people. Boy have we flipped things upside down or what in the last 20 years?

It used to be that people showed their status by how much time they took off for vacations or how many people they had to do certain things for them. Today it is the opposite. NPR reported on a study that shows people perceive others to be more important and of a higher status the more those people are, or at least seem to be, busy. Even people on the lowest end of the socio-eonomic ladder viewed those within their own level as higher status if they seemed to be busier. This is even accounting for people who don’t have a choice and have to work multiple jobs just to pay the bills.

What happened to the nationally agreed-upon standard of working hard early on so that you didn’t have to be so busy later in life? This is, in my opinion, one of the insidious natural consequences of the information age. As we have more and more information and connectivity at our fingertips (or thumb swipes), we are naturally, even often unwillingly, drawn to look at more and more at a surface level only. Going deeper into the information to get at real meaning, or going deeper into a conversation to find out why someone is hurting, rather than just knowing that someone is sad, takes time away from finding out yet even more information.

We do not realize how being aware of and seeking out lots of surface level information (Kathy got a new adorable cat; Bob’s girlfriend broke up with him; Janelle went to the Bahamas for Denise’s destination wedding; Tony’s kids both made the varsity this season; etc etc etc) is not only nearly meaningless in any of our personal and professional lives, but actually harms our relationships because staying busy for status prevents us from doing the really deep thinking and making the really deep connections that drive societies and excellent businesses to succeed over long periods of time.

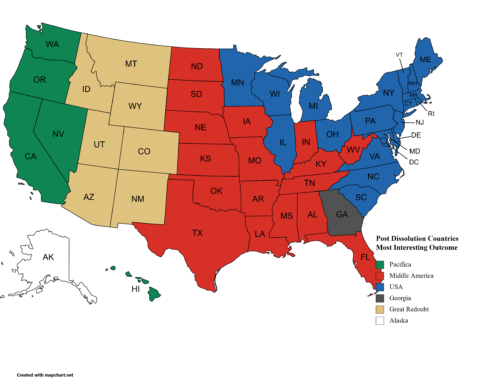

If we merely follow busyness out to an easily thought-out logical conclusion, we can see that it could result in a societal collapse from within. Yes, really. This isn’t some dystopian prediction, but a reasoning of what happens if everyone were so busy being busy that they had little time to think things through. We’re already so busy following Twitter and Facebook and making our LinkedIn profiles get the most views, and checking all day to see how many views they have, and liking other peoples’ posts, and staying later at work every day to show the boss that we’re really busy, that the building blocks of sociology and economics cannot possibly be accomplished as there is no time.

What are those building blocks? Relationships.

Relationships take time and effort. Time we don’t have when we are busy being busy. Relationships that build social capital and are not transactional. That means doing things for their inherent worth and not for some expected favor or return on your time investment. Helping someone in the office because they need the help, not because you expect to call in a favor down the road. Helping someone on a project with your skill set even though your name won’t necessarily be on the glossy cover of the project promo.

In UltraSociety, Peter Turchin discusses studies showing how companies with cultures of internal competition, like Enron had, fail at far greater rates than those who foster cooperation towards common goals. The same goes for sports teams. But that cooperation cannot be had when everyone is too busy to take the time to know what their coworkers need or if they see those people as their competitors for promotion.

In his classic Leisure: The Basis of Culture, Josef Pieper warns us that “not everything that is more difficult is more meritorious.” Pieper originally lectured on this topic after World War II and his lectures became the basis for the book. He was visionary enough to predict 60 years into the future what issues we would struggle with. He said that man would be pushed to create a state in which there was “total work” and that such a state would have little to no room for leisure, for people to think and contemplate on how things ought to be.

And when you look at our world today, it is easy to see that as a societal norm, we value busyness and giving ourselves more wholly to our jobs and the work of being busy than we do to our families and our relationships.

The chillingly predictive busy worker that Peiper discussed is the “functionary” with the one-track mind that only finds his satisfaction in service to the firm. He said that this functionary buys in to the notion that his life is only fulfilled in the service to his busyness and hard work, but at the cost of spiritual impoverishment. How many of us can look in the mirror and say truthfully that this isn’t us or wasn’t us at some point?

Leisure, Pieper points out, is not the result of vacations, weekends or spare time, but a mental and spiritual attitude that prioritizes the long-term (many would argue eternal) relationships over short-term busyness. And worst of all is when you are placed in a position to make it an either-or decision. It isn’t. You can work hard and serve your country or firm and still make your leisure time for relationships, reflection and personal growth.

Whether it is investment, coaching soccer, seeking promotion, or keeping ahead of your “friends” on social media, try to step away sometimes and ask yourself whether you intended from the outset to always be busy or whether you wanted at some point in the past to have the time to enjoy the fruits of your busyness.

You can make the change. Really.

Keep thinking.

Great article! I wonder if another way that social media damages our relationships is that if we see someone’s update, we then took away something to talk about in person.

Rand, it seems to me that if we see something someone else posted and we then go discuss that with someone else, that would probably be a good thing. Even better would be to tell someone something you learned that changed your mind or that you didn’t know before.