By Tom Ruby and Scott Bethel

Back in the first week of January, Tom posted some specific predictions for what the world would see in 2030. Not yet half a year into that decade, the Coronavirus Pandemic is accelerating some of those predictions. Sure, there were people who predicted that a pandemic would wreak havoc in a globalized, interconnected world. Kudos to those who accurately predicted this would happen. But it is no surprise that there is wide variance in how countries have and are responding.

Many people are surprised at how willing populations are to accept social distancing and self-isolation. But history shows us that, at least in most Western countries, people realize that societies can only survive when peoples’ individual decisions are informed consideration for the society and not solely the individual. We cannot choose our calamities. But we can choose how we react to them. And we see today that while some react with independence, defying government recommendations for social distancing, norms are rapidly evolving in a direction to best affect the entire society.

This virus will run its course through the global population whether we distance ourselves or not. That is just a mere recognition of scientific reality. Click here to see a simple, but very telling graphic, which you can adjust by time, to see how the rate and number of infections and deaths changes as the length of intervention is adjusted. What you see is that both the sickness and the cure are awful. If we do nothing, the most number of people die in the shortest time. And while some will think that will offer us the best chance to get the economy going again, that fails to recognize the impact of those certain deaths on the recovery itself. For example, what impact would it have on recovery to lose a significant percentage of doctors and nurses, truck drivers, assembly line workers, etc. and aside from virus-infected patients, how chances would the millions of people who enter ERs with heart attacks and strokes every year have to survive when those ICUs are filled with virus patients?

So while most people are rightly concerned about how to get out of this pandemic in the shortest time with the fewest deaths, leaders of businesses, industry and government need to start thinking about how they will lead when we are in the clear with very real changes to society that have been revealed by this crisis. Lets talk about some of those.

First, there is a genie that has been let out of the bottle by necessity that leaders will not be able to coax back inside. That is working from home. Absent a health crisis, it is fairly easy for businesses to require employees to come to the office to essentially monitor their time. Furthermore, any number of studies show that social pressure, especially among men, pushes them to be at the office to signal to co-workers they’re busy, when they could be as or more productive at home. But today, to save their businesses, industry leaders have collectively undertaken the largest work-from-home natural experiment in human history. Suddenly, the presence-based metric has changed to a performance-based one. The same goes for college and K-12 schools. Let there be no doubt on this point, empirical evidence will be available in abundance at the end of this pandemic.

If the financial numbers show anything close to similar earnings after the crisis as before, adjusted for peoples’ ability to buy given being laid off from jobs, then business leaders will find it almost impossible to justify why their people need to come back to the office other than for specifically justifiable requirements. Furthermore, CFOs will insist that spending money on massive office complexes is a waste given that their employees can work from home. We foresee a very large percentage of corporations scaling back their office spaces to a fraction of what they were pre-Corona. Corporations can offer their employees benefits to offset a portion their own utilities to work from home and thus not have to pay for expensive office complexes. What kind of ghost town would Crystal City, Virginia, look like if corporations paid their people to work from home. The next economic and intellectual puzzle would be how to repurpose this mega office complexes ubiquitous in all metro areas.

Second, colleges and universities will face a reckoning. A very large reckoning. Thus far no colleges or universities are still open for in-person classes. And most have decided that the remainder of this school year will be done on line with professors creating on-line content including videos of their lessons and fielding questions from students via e-mail or some video-conferencing capabilities. Unsurprisingly, most schools are offering some pro-rated rebates or vouchers for future semesters to their students for their housing and meal plans. But so far few if any have made any offer to their students to reduce or refund their tuition based on not having classes in person. This will be the issue that will drive a massive shift in higher education after the Pandemic.

If elite private and public colleges and universities continue to claim that their on-line education experience is worth the same cost as in-residence learning, which they are de facto claiming this semester, then there will be little reason for future students to spend that kind of money to attend in residence from Harvard or Stanford or Middlebury or Centre when an on-line option is available at a fraction of the cost. This is a certain and foreseeable implication of this Pandemic that will drive all institutions of higher learning to recon with. We should expect a wide variance of how they will structure educational options. This will create a true marketplace unlike the one we have now.

Third, social habits will drive new norms for how people congregate and how they act when they do. In Asian countries wearing face masks prior to Covid-19 was not only accepted, but largely expected when one is ill and at risk of passing on an illness to others. It is seen as the responsible way to protect your fellow members of society. In the West, face masks are so rarely worn as to nearly be a taboo in public. People largely accept that there is some risk of catching a cold in public spaces. That risk acceptance is based on low transmission and mortality rates of the flu. But with the Coronavirus today, and the near certain risk of other viruses perhaps unknown today spreading rapidly in a globalized society, wearing masks will become normal, either under direction of doctors or on peoples’ own cognizance. So will wearing gloves when shopping and pumping gas. So will a move away from shaking hands to some other form of greeting, most likely a slight bow of the head, the tipping of a ht or a slight salute-like acknowledgment. The exact form isn’t as important as the fact that we will likely move away from shaking hands.

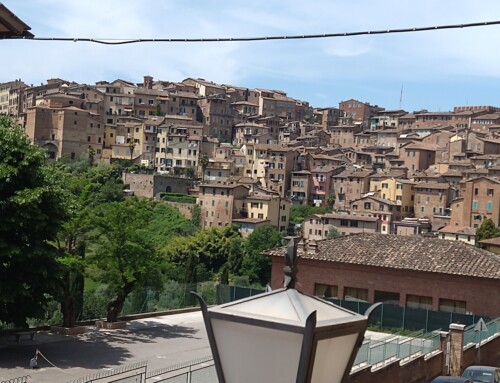

This movement away from touching will have deep implications for gatherings from seating at sporting events to concerts, to street festivals. One cannot imagine concerts like Lolapalooza without a Mosh Pit, or densely packed football stadiums, or Munich’s Oktoberfest, or crowded markets like Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar continuing as in the past when deadly contagions spread so easily in those very conditions. But they will go on, perhaps with modifications like hand sanitizer everywhere and only merchants being allowed to handle merchandise.

People will not stand for permanent universal social distancing. Almost certainly people everywhere will accept risk of contagion during the summer months when there are no reports of outbreaks. People will likely accept risks of gathering at sporting events and Christmas festivals even in winter as long as there are no reports of outbreaks. People will expect and socially enforce a new norm of staying home if you are sick in any way. You do not want to be the person sneezing in a crowd. You will be shamed and pointed at and yelled at to get away and go home.

Air travel likewise will be forever altered. Imagine the lengths to which airlines will go to assure passengers that pathogens that are trapped in the endlessly recycled air of a transatlantic flight will be filtered. Who hasn’t boarded an airplane and noticed someone in an adjacent seat coughing or sneezing their way from point A to point B? It is doubtful that an airline ticket will be denied without a clean bill of health – but like an intoxicated person is asked to leave a flight before takeoff will a person suspected of being sick be asked to leave? Will air travel be the first thing curtailed in the future if an outbreak of pandemic be declared to isolate the disease in the country or locality of origin.

What people will stand for and expect, however, is a rapid and universal shut down of such close-proximity events as soon as an epidemic breaks out anywhere in the world. Coronavirus has taught us that once an outbreak is recognized anywhere in the world, its likely vectors have already spread to countless locations in all directions. That means that as soon as a serious outbreak is detected in Shanghai, people will expect all air travel to and from China (or wherever the future outbreak manifests) to halt and people to self quarantine probably all over the world for a 2 week period, with perhaps as much a month of isolation of the epicenter. People will come to accept and expect that it is better for periodic short-term global shutdowns than it is to live through periodic global pandemics.

Sports leagues will begin to build and implement contingency plans in which players, coaches and staffs are kept apart from possible vectors of contagion and entire leagues are medically certified as clean so that they can continue to play even in empty stadiums in order to keep revenue flowing from broadcast rights. Likewise, concerts and music festivals may be mostly be held from mid-summer (after all traces of contagions are most likely to fade away) until mid-autumn (before the next contagions are most likely to break out). In those countries where the culture of close, densely-packed marketplaces flourish, we predict we will see a variance in which some counties forcefully disband existing locations and set up new ones with more distance between stalls. Others will continue to accept the risk and will live with the consequences whatever they be and however often they arise due to cultural demands or a pure need to sustain the open market barter system to empower the economy.

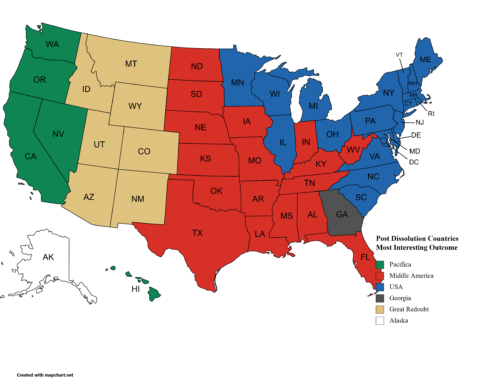

Not all countries will be able to make societal changes at the same time or at the same pace. That means there will be a “have and have-not” component to any pandemic response. Countries or industries with largely developed work forces of office-based executives have the luxury of transitioning to a work from home environment (discussed above) while primarily labor-based countries or industries will have to accept a certain risk because there is simply not a work-from-home option.

Countries, states and municipalities will rapidly make decisions to shut themselves down and cut themselves off and this will be expected and accepted. In the future there will be little benefit of the doubt given to those leaders who hedge their bets or wait to see if it is really bad before acting. Of course, that could mean false positive responses which will slowly erode confidence in preemptive closures. However, because we will also likely see far more of these types of pandemics in the future, that public confidence in early closures of borders will be recharged periodically when outbreaks arise and are safely contained.

A key component of knowing when an outbreak is about to become an epidemic will be the acceptance of near-global monitoring by governments and corporations. We see that already today to a large extent. Whatever caution there is against ubiquitous tracking of individuals through their mobile devices will evaporate as soon as elected official hear from their constituents that the people are fine with having their locations known if it will keep them safe. That was the rationale for establishing TSA and we now all accept waiting in long lines while our persons and our belongings are scanned. Detailed location tracking and contact tracing was what helped South Korea lower the transmission and mortality rate fairly quickly. Likewise, the North America public will readily agree as a society that if governments can use our location data to know when a pandemic is about to break out and perhaps prevent it, people will be ok with their data being used that way by governments regardless the intrusiveness and loss of privacy.

Fourth, there will be an aggressive analysis of assumptions by businesses and governments. This will be the greatest test and opportunity for businesses at all levels as well as governments local and national to seek out and recruit thinkers, planners and methodologists to help them go through the process of analyzing and validating their assumptions. So what are we talking about here? Lets look at some of the most fundamental assumptions we had as a society that proved to be false at the beginning of this Covid crisis.

We assumed that our tests would work. But the tests sent out by the CDC had faulty negative controls. The US was late to get into the regime of testing to begin with. And then it took time to realize that the tests were faulty. Testing is not simple. Not anyone can develop a test. And there must be a process of assurance that the tests which are produced are accurate. By the time the CDC put out a call for independent labs to begin making their own tests, we were so far down the road of contagion that the goal of slowing the rate of transmission through testing and isolation was already lost. Now, so many people are infected that until a blood test is developed to detect antibodies and is widely employed across the country, we will never truly know what the true extent of infection is and we will be left to only treat the suffering.

Another missed assumption was that people will believe that this was a true pandemic with dire consequences. Epidemiology is all about numbers and patterns and probabilities. It isn’t so much about specific individual predictions as it is about the sum and average of those predictions. The Washington Post reports that perhaps the greatest missed assumption was that the pandemic would be politicized and people, most notably the President, would call it a hoax. Public trust is a powerful variable in any situation that requires interaction. From money being worth what we think it is worth, to the belief that the fire department will show up if your house is on fire, to there really being a threat of pandemic when the CDC tells you its real.

But when the President says that the doctors and scientists are part of the deep state and are purposely making it up to make him look bad, a significant portion of the population will ignore the threat and go about with their lives as normal. They thus put the whole society at a risk they wouldn’t have had to endure if everyone trusted that the outbreak was real. And coming on the heels of impeachment, in the midst of a Presidential election campaign in which a major pillar of the Democratic party is to show the President’s lack of leadership ability, it makes sense that a large portion of the political right might question the media’s motives. As Ross Douthat pointed out in the New York Times, the media’s initial message was one of tamping down the threat so as not to make this a racial event because of the virus’s origin in China.

By today, almost nobody believes that Covid is a hoax, but by now the damage has been done.

A third faulty assumption is that our deliberately-created just-in-time logistical system for all goods and services is sufficient in cases of national emergency. Over the past 20 years, corporations and governments have realized that our logistics infrastructure and our inventory algorithms are so advanced that it is more efficient and cost-effective to order items as they are needed to show up when there needed specifically where they’re needed rather than to keep inventories of spares in leased warehouses. Hospitals spend money on supplies and expect them to be delivered as they are used so that there is always a steady state of just the right amount of masks and ventilators on hand for the demand at that specific facility.

What this means that at any given time in the logistics-chain there is a limited (read next to zero) amount of shelf-stock and excess inventory. By design, products on the shelf are those required for the immediate future. The era of the “in the back room” is over – most stores have only a transition area near the loading dock – all the product is on the shelf. Will there be a requirement to stockpile certain essential supplies for the completely unexpected? Will entities with excess (such as respirators in the current case) will be compelled to provide unused capacity to other localities in need – as opposed to holding onto to their resources anticipating the requirement to come their way.

But as we all see now, this fails utterly in a pandemic. Math is without emotion. It doesn’t care that people are suffering and that more will suffer int he coming weeks. Math tells us that the system which we deliberately designed for efficiency in steady-state operations cannot meet future demand when the amount of required equipment exceeds the manufacturing capacity to build it. And furthermore, when you factor in that much of the manufacturing capacity upon which we rely is located in China, we add multiple other variables beyond our control into the equation.

This reckoning with our fundamental assumptions will affect us all in ways few will recognize now. For example, insurance companies will begin to differently assess risk, which will mean that for some activities, your insurance rates will go up. For others, they will make decisions on where they live based on different assumptions. That means that many smaller towns and cities can and should expect to see an increase in people moving there from larger metropolitan areas like New York or Chicago or Los Angeles.

This will necessarily strain local cultures as people with differing political and social views move to an area not for its culture, but for its perceived safety in times of trouble. Or suburban distances will increase with people wanting to stay near the amenities and culture of a larger city but have more room between them and their neighbors. This will put an additional strain on the road and transportation systems. Unless of course our assumption of increased work-from-home will be the norm and a more evenly distributed population will be the result.

We can also expect governments and corporations to question how such an event as this pandemic would be different if there was a simultaneous natural disaster such as a hurricane, earthquake or solar storm resulting in a power outage. Life in isolation is difficult enough with power. But without power things get harder more quickly and we lose even more people more rapidly and for a longer time.

There are so many more assumptions that corporations and governments will consider in the months ahead and we can’t go into all of them. But here is one for everyone to consider. As people from China to Italy to the US have stayed home during Coronavirus quarantines, air quality around the world has dramatically increased. a conservative estimate considers 50,000 Chinese lives saved from cleaner air. That is far more than died from this pandemic. Air quality in cities around the world is improving markedly when commuters stay home.

It will be not just a legitimate question to ask, but perhaps a necessary one: Can the money we save from paying for the consequences of global pandemics be spent to improve mass transit and mass connectivity so that people can work from home as a matter of course, and those that must travel do so by clean mass transit. The savings from lives lost due to pollution could literally pay for this effort.

We tend to see the cost-benefit decisions only after they have played out for many years. For example, the money spent on the global war against terrorism has been shown to have been enough to repair or replace a large percentage of the entire highway infrastructure in this country over the last 20 years. We cannot determine how many, if any lives were saved in the War on Terrorism. Likewise, we cannot go back and unspend that money and we cannot argue that it has made us truly as safe as we intended it to make us.

In the midst of this pandemic, we can now clearly see choices that we have not made and how they would impact us if they had been. This is what wise business and government leaders will do in the near future. Life, both individual and societal, will change in the coming months and years. Those who figure out how will do well when it does. Those who shape that change will be in high demand. Those who shape it for good as opposed to for personal gain will be the saints.

Tom Ruby is CEO of Bluegrass Critical Thinking Solutions. He is a retired Air Force Colonel with a PhD in Political Science from the University of Kentucky.

Scott Bethel is CEO of Integrity ISR. He is a retired Air Force Brigadier General with masters degrees and fellowships from multiple institutions.

Leave A Comment