by Tom Ruby and Scott Bethel

We’re now half a year into the Covid-19 Pandemic. So much has changed and so many experts have missed the performance or integrity cut that few people can be certain they have confidence in what is real and what isn’t. Now is the time for business and government leaders to assess whether we are on the path to make it through the pandemic healthy or whether we’re about to fly into a mountain. And its foggy. And turbulent. Murky and unstable air ahead. Let’s reassess this together.

The focus of what we are talking about here is not political decisions. It is not about leadership successes or failures, and its not about which team is better going forward after November. What is important to discuss here is some considerations for making better choices in the future – and by future we mean weeks and months. It is clear that the United States was ill-prepared for a true pandemic and we are now living the consequences. The sequence of decisions – both action and inaction – are what propelled us to this place. We are where we are today and we can’t change that by merely pointing out past mistakes. We can and should, when appropriate, discuss how different decisions months ago might have altered our courses, but only insofar as that is helpful for recognizing those same moments now and correcting our course for the future. There will be innumerable after action reports, hearings and board meetings, and very likely, recriminations. There will be the inevitable books, all with variations on the title “If Only They had Listened to Me.” The real question for leaders is what can we do now to make a difference in the near term?

To begin, we’d like to point out that this pandemic was not only foreseeable, but foreseen by many. The point isn’t that some made the wrong bet, but that this kind of event is out there and lots of people see it coming. Because it hasn’t happened doesn’t mean it can’t or won’t. Assign someone in your organization or business who you trust to think about and research the playing field for opportunities and threats. In this case we mean an unanticipated but existential threat to your organization. The pandemic is not the only such possibility. Included in your planning should be pandemics, natural disasters, political turmoil etc.

And you should do this not just every 5 years when you update your strategic plan, but at least every year. Preparation is rarely expensive. Having a meaningful plan to cope with a catastrophic event in your business is about thinking through the challenges and possibilities. In some cases there may be material requirements but mostly you need a plan and the discipline to follow it when called upon. And then most importantly, act on the information you are given. Hiding from the inevitable won’t make it miss you.

While many leaders have commented on the fact that China did not provide a clear understanding of the severity of the outbreak in Wuhan and beyond, the data even then told a clear story for those who looked and thought it through. This led to uncertainty and perhaps a delayed political response in the rest of the world. However, when the first signs of this pandemic started slowly rising to the level of daily media noise, some epidemiologists and others who study societal trends realized quickly that we were on the cusp of an explosion. The very globally interdependent economy would soon see these few detected cases become a raging wildfire of pandemic worldwide.

Some prepared the best they could by ordering stocks of materials they’d need before competitors realized there was even an issue. Many businesses and entire industries, such as hospitals and health care networks realized very quickly that just-in-time logistics cannot be relied on when very few manufacturers are suddenly inundated with orders from around the world while the factories that make the products are shutting down with sick workers. Most public health officials worked their normal bureaucratic channels to distribute existing supplies and ramping up manufacturing of additional material. Others hoarded what they had realizing they could not buy replacements. In short, the size and nature of the emergency and what would be required was grossly underestimated. Local authorities expected the State to do something. States expected the national government to respond. Meanwhile the pandemic spread. It just kept going.

Regardless your segment of business, industry or government, you will be faced with a simple but important, two-sided consideration. If you wish to be able to ride out a sudden hit to your logistics system, then you need to pay the price of maintaining sufficient inventory to take you through whatever crisis you can foresee. that means keeping an appreciable amount of inventory on hand for such an emergency and rotate stock to ensure quality an usability. If you are unable to do that because of low margins or you’re willing to accept the risk, then you’ll be in the same boat as everyone else and may have to let your promises on what you can fulfill slide to the right on the calendar and hope your relationships can weather the storm.

The situation will eventually resolve, but the landscape on the other side may be very different from the one you played on before the crisis. Your supplier might have gone under and you end up waiting in line with others hoping to get some materials while the remaining players take months or years to build up new capacity. It is even more important to be agile enough to shift suppliers and partners AFTER the crisis has passed if required. To restart, sustain, and perhaps even increase production may look very different from today’s block-chain enterprise. Contingencies must both be evaluated and exercised to determine their viability.

These are not all easy choices. But, if businesses and governments are to survive and thrive, then strategic planning for existential crises is an absolute MUST and options must be evaluated in advance. Many of the decisions our leaders have made during this crisis have been reactive. Reactive decisions generally are of poorer quality and because of timelines do not allow you to explore all the variables which affect the situation. Having a plan that is known, tried, and evaluated in advance nearly always beats one developed on the spot. Your survivability depends on thinking through these potentialities. Businesses may have to accept making a choice to work at the margin and have nearly no room for the unexpected. But those that do probably shouldn’t sign a long term lease.

Many economist and business leaders are concerned about the economic loss. Market Watch predicts the costs of the pandemic have not been fully established but are in the $19.9 TRILLION range over 5 years. But it isn’t only monetary costs we ought to consider as leaders. We need to consider the cost of a massive demographic change. Low birthrates will necessarily drive changes to business opportunities, not just insurance actuarial tables. As fewer people are born and enter the workforce, fewer taxpayers are available to pay for programs that ever more people are demanding. With more people dying of the disease than would from all causes in a normal year, this demographic trend must be taken into account for long-term plans by businesses that order materials and predict sales based on population.

When that lower birthrate kicks into affecting economic power in 20 years or so, it will necessarily impact downstream variables such as poverty and health and not just birthrates in the US. What has been for the last half century the world’s leading consumer economy, will have ripple effects on globalization writ large. As the Washington Post wrote, “The pandemic is interrupting the flow of workers, money and goods that increasingly bound the postwar world, helped to lift more than a billion people out of poverty since the fall of the Berlin Wall and delivered unprecedented stability and prosperity to much of the planet. To encapsulate: U.S. investment in China raised demand for soybeans that enabled Brazilian farmers to buy German cars.”

Businesses and governments should now be basing revenue projections, purchasing power and consumer demand on the factors the pandemic has dropped in our laps as opposed to numbers from last year before the pandemic. How seriously a business or government leader takes empirical evidence into account ought to factor significantly in a corporate board’s decisions for hiring and voters electing their representatives.

It is a modern miracle that globalization has helped lift over a billion people out of poverty worldwide. In 1975 half the world’s population lived in extreme poverty. Today that number is about 1 in 7. much of that decline is due to the effects of globalization. But if trends continue as they have the last four months, the whole world could be in trouble. Global economic integration has been severely impacted by the pandemic. In fact, in many places it has come to a near halt. And most countries are considering how to protect their own economies.

Should economic nationalism continue to trend in the same direction and if people around the world stay close to home and are unable or unwilling to fly around the world, and if restaurants continue to close at the rate they have been, then a significant portion of the global workforce will go from adding to their local economies and supporting healthcare and public works to drawing upon services that will be both more intensely drawn upon and at the same time less funded due to decreases in tax revenues. Add to this mix the real possibility of another financial collapse that could be worse than in 2008, and there will be far fewer options for business and governments to borrow.

In the last two years the world economy and in particular the US economy has been strong. Any analyst predicting the possibility of another Great Depression might have been laughed out of a room. Today those predictions must be taken seriously if you are to be recognized as a good steward of your people and resources.

You must also be concerned with visibly taking seriously, both in word and action, predictions about your future environment and the necessary the consequences of present actions. You have to consider the importance of the need for people to see that you take the situation seriously. For example, taking temperatures of those entering your work spaces can have a profound effect on the seriousness by which you take your worker’s safety. On the other hand, you must take into account that a large percentage of people who are presently contagious will not show any symptoms and can therefore unknowingly spread the infection. You have to consider how to mitigate against those realities. It doesn’t mean you don’t take temperatures. That is an important signaling mechanism to people about your seriousness; that you can be trusted in other areas of business.

You also ought to call someone in to help you think through what your labor availability will look like in the next several years as well as the market for your product. If you are a small college which bases its budget on full tuition that out-of-state and international (largely Chinese) student enrollment provides, you will have to consider how to pay your faculty and staff when those students aren’t available. If you’re a bank in Los Angeles, Nashville or New York who has home or equity loans out to freelancers who work in those artistic communities, you must consider how to deal with those clients when they are unable to pay their loans because they lost their jobs. The bottom line is that you must be aware of the changes in the market place both in terms of your raw materials and people as well as those that affect your product. What the pandemic has brought home to many is that the landscape can change dramatically and lack of plan to cope with those changes has a high chance of resulting in disaster.

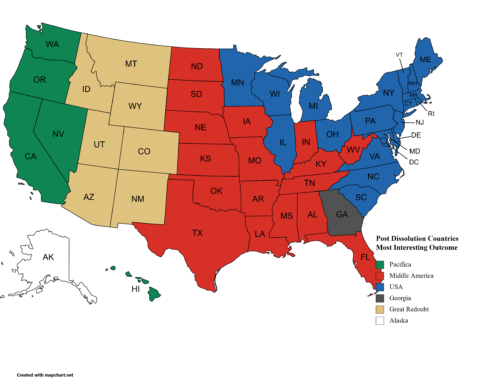

Even if the predictions of the Second Great Depression comes to pass, the entire global way of life that has emerged over the last 50 years will not suddenly come to a crashing end. At the height of the Great Depression 70% of workers retained their jobs. While the prospect of 30% of the population going without work for an extended period of years would actually devastate the economy and change our way of living as a whole, there will still be work for most, meaning that we can and will get through the crisis. Bruised, certainly. Bloodied, perhaps for many or most. But the country and the world will recover. It may be slow and will likely be a quite different reality than we had before. There may be changes few foresee, such as the collapse of some countries, a degeneration of entire cities to real hopelessness, and families moving in with relatives into something wholly unfamiliar in this age, but more closely resembling the extended families of our history until before World War II. Businesses will hire employees to meet demand as it build back and do their best to expand the economy.

We should also be realistic with what such an economy could look like. It took humanity until the end of the last century to build a global economy in which intellectual capital held such a strong position and its purveyors commanded such high salaries. It took till the end of the last century for actual production of material goods to require such a small proportion of laborers and for that manufacturing economy to shift to a service industry that was so susceptible to economic downturns. The result is that a foreseen pandemic wipes out jobs and opportunities at both ends of the economic scale and the people who lost those jobs may be unable, even if they were willing, to shift into new jobs because of travel restrictions or inability to pay for a move, housing and job search.

Business and government leaders cannot pretend that the fragility of the system they created was not a necessary byproduct. That is done. They must consider how to go from here. Funding industrial foundations to lure factories is good. If those factories build and hire local workers. But if the global trade that the factories are based on is interrupted or halted, then that money is sunk and irrecoverable.

Leaders today are in perhaps the most precarious position since the last Great Depression. They cannot punt and leave decisions to their successors. They might be right or they might be wrong. But they must decide and act.

Think it through. Call for help. Be inquisitive. Play out all your assumptions to their logical conclusions. You can do it. As James Fallows writes in The Atlantic, every catastrophic accident has a chain of events that can be broken to prevent the accident. When accident investigation boards look back, they do so with precision to the facts and leave out emotion. Do the same thing today but looking forward.

Keep thinking.

Leave A Comment